Young Literacy Learners Take Center Stage

By Mary Jo Fresch

I began my teaching career as a third-grade teacher in 1974. The district reading program was a synthetic phonics series. I regularly had students required to repeat the second-grade reader because they had failed to keep pace with their peers. These students needed constant support to progress and hopefully “graduate” to the third-grade reader. By the end of my first year, I knew the series was not creating successful readers. The focus seemed to be exposure instead of mastery.

I faced an equity issue for my students. I needed to hone my ability to recognize proficiency differences and address individual “bottlenecks” in literacy learning. And I needed to bring the joy of reading to my students.

Unlocking what students can and cannot yet do

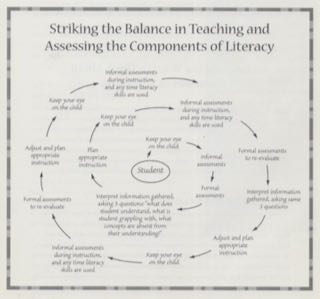

My undergraduate program included one course in teaching reading, just enough to skim the surface of what a primary teacher needed to know. I realized a reading specialist master’s degree would benefit my students and me. That coursework turned the tables…instead of focusing on materials, flashcards, and games, I focused on students. I discovered ways to peek into the head of a learner struggling to read words, read fluently, comprehend, and build vocabulary. Years later, a Ph.D. in Language, Literacy, and Culture solidified my belief that teachers must focus on what the student can successfully do and plan engaging, joyful activities to nudge new learning along. While teachers need to address the scope and sequence of reading skills, they must “keep an eye on the child” to strike a balance between teaching and assessing. What are students telling us they almost understand but not yet? The answer to that question is the sweet spot for planning lessons that challenge but do not frustrate them.

From: Fresch, M.J. & Wheaton, A. (2002). Teaching and Assessing Spelling: Striking the Balance Between Whole-class and Individualized Spelling.

Language learning for young readers

Literacy development in reading, writing, and word knowledge occurs in sync – that is, they are parallel processes. Each informs the other and addressing all of them as students learn is critical. When you think about it, writing is easier than reading. Let’s say a student is trying to write elephant. Knowledge of letter/sound relationships will help students predict the spelling. (My personal campaign is for teachers to not refer to students’ unconventional spellings as invented – rather they are predicting the spelling based on their current operating knowledge of the language. These predictions will change as students experience more print.). So, the student may write lefan or elufint – allowing us to observe current understandings and plan instruction. But, if that same student comes across elephant in text, the work is much harder to lift the print from the page. They need to know something about short vowels, the ph sound, the nasal nt, and multi-syllabic words – and which of these might be the stumbling block is up to the teacher to assess.

Giving students strategies to decode is essential to make them independent readers. They need knowledge in letter/sound relationships and how to consider what might make sense both contextually and semantically. Thus, my work over the years has turned to helping students understand how English works. Power over the language provides independence in reading and writing. “Immediate” word identification aids in fluent reading and allows the reader to focus on comprehension. The need to “mediate,” or pause and consider what a word might be, distracts the reader from understanding the text. Accurate and automatic decoding are fundamental to comprehension. When we assess (by the way, the Latin origin of assess means “to sit by” – exactly what we do when we are “keeping an eye on the child”), we can observe the strategies students can rely on and which they need scaffolded.

Recently David L. Harrison, Tim Rasinski, and I partnered (in press) to write a two-book series for Scholastic. By combining Edward Fry’s list of 38 common, high-frequency phonograms with Wylie and Durrell’s list of 37 we created a powerful list of 52 rime families. David wrote poems, Tim created word ladders (one focused on phonics; one on vocabulary), and I wrote a wide range of language arts lessons. Students can learn hundreds of words through examination of word families and have a powerful strategy to decode words. David and I also partnered (2020) to create a book that focused on fun and engaging aspects of the English language (six types of “nyms” such as acronyms, eponyms, synonyms, retronyms; similes; metaphors; idioms; shades of meaning; and word origins). In all of this, the heart of my work is to make language memorable, rather than memorized.

We pique students’ interest in language when we are curious about words. That interest will have them looking at words in new and memorable ways. This also means they will take what they know into writing. When students ask why the “silent/magic e” doesn’t make the vowel long in words such as love, I often hear teachers say, “that’s an exception.” But there really is a rule…English words do not end in “v.” Over time, the “e” was added to those words, but the pronunciation did not change. Once you tell your students that story they will not only remember to add the “e” but will be digging through print to see if they can prove you are wrong. What a fun way to solidify the “rule” and get them engaged in self-selected print to build confidence!

In sum, you can be assured that I say, systematically follow a scope and sequence, but do it in fun and engaging ways that take the individual learner into consideration. Give students independence in unlocking the language. We can never memorize every word, so let’s find ways to make language memorable. Texts that play with words and make students want to read and reread builds skills and confidence. Writing self-initiated texts puts their operating knowledge to work (and on display for your formative assessment). Discussing about what we read makes students understand we are about “word recalling” and not “word calling.” And all of these put our young learners at center stage…exactly where they should be in our classrooms.

References

Fresch, M.J. & Harrison, D.L. (2020). Empowering Students’ Knowledge of Vocabulary: Learning How Language Works (Grades 3-5). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Fresch, M.J. & Wheaton, A. (2002). Teaching and Assessing Spelling: Striking the Balance Between Whole-class and Individualized Spelling. New York: Scholastic.

Harrison, D.L., Rasinski, T. & Fresch, M.J. (in press) Partner Poems & Word Ladders for Building Foundational Literacy Skills: Fluency, Phonics, Phonograms, Spelling, Vocabulary, Writing, and More (Book 1 – Grades K-2). New York: Scholastic.

Harrison, D.L., Rasinski, T. & Fresch, M.J. (in press) Partner Poems & Word Ladders for Building Foundational Literacy Skills: Fluency, Phonics, Phonograms, Spelling, Vocabulary, Writing, and More (Book 2 – Grades1-32). New York: Scholastic.

![]()