Libraries that Create a Community of Readers

By Brenda Krupp & Lynne Dorfman

It’s All About the Books: How to Create Bookrooms and Classroom Libraries That Inspire Readers (2018, 21), authors Landrigan and Mulligan state, “The classroom library is the home of the class’ reading community . . . . Its primary role is building a literacy community in each classroom and ensuring that each student is a member” (21).

Classroom Libraries are Essential

A classroom library is often the hub of the classroom. According to the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE), “All students must be able to access, use, and evaluate information in order to meet the needs and challenges of the twenty-first century….Reading in all its dimensions – informational, purposeful, and recreational – promotes students’ overall academic success and well-being.(Position Statements: Statement on Classroom Libraries, 2017).” Books are often arranged in easy-to-navigate categories such as favorite authors, fiction and nonfiction, genres, themes, and topics that relate to across-the-content area reading. Shelves are arranged to showcase books students want to read and ones the teacher has researched and knows will meet the needs of the readers in the classroom. A well-stocked classroom library will give all students access to relevant, engaging texts (fiction and nonfiction) and magazines that represent their diverse identities and reading tastes.

The Top Ten Benefits of Classroom Libraries

- Students’ motivation and engagement increases by encouraging voluntary and recreational reading in school and outside the school setting.

- A wide range of reading materials that reflect reading abilities and interests of the class is at your students’ fingertips.

- Choice in self-selecting reading materials for self-engagement is a key factor.

- Enhanced opportunities for assigned and recreational reading encourage students to bookshop often.

- Immediate access to texts will keep reading a top priority in the classroom community.

- Classroom libraries can personalize book choice that reflects the students’ favorite authors, interests, and genres within the classroom.

- Teachers can curate the library to introduce new authors and genres with a comprehensive assortment of books that support individual reading, book club reading, inquiry projects, and classroom discussions about current topics in our students’ world outside of school.

- By having a voice in what materials will be in the library as well as how the library is organized and arranged, students have myriad opportunities to create a space for books within their classroom they want to use and will use.

- As books are weeded and replaced, these books become available for students to select and keep. Book ownership often increases reader engagement and skills. Having books in the home is an important part of raising and sustaining a student’s reading identity.

- Reading widely and often builds students’ vocabulary and background knowledge, giving them a chance to use their reading strategies to make meaning of texts across the curriculum.

A Classroom Library Collection Reflects the Community Members

Texts can provide a sense of belonging for all students. When books reflect the cultures and experiences of the readers in your classroom, they provide a welcome experience and allow readers to connect to what they are reading on a more personal level. When the books in our libraries are inclusive and socially conscious, students develop awareness, empathy, and compassion for others by learning about cultures and customs they may not experience in their own community. Books can also create opportunities to celebrate cultures and experiences that are like and different from their own. If classroom libraries contain books that reflect the world we live in, students have the opportunity to see themselves as a part of this world, learning how to navigate and participate in a global community. Listen to Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop talk about windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors here: Mirrors, Windows and Sliding Glass Doors

Curating a classroom library that is timely and relevant takes time and effort on your part. Websites such as We Need Diverse Books, Colorin Colorado, and Jane Addams Peace Association are three places to start. Be sure to use NCTE’s journals (Language Arts and Voices from the Middle) and ILA’s The Reading Teacher, which regularly highlight new texts. An important resource will also be your school and local librarian, but always try to be the first reader of books you add to your classroom collection.

How to Highlight the Books in Your Library

Highlighting the books within your library will build an excitement for more books in your library. As the teacher you can promote books you think your students will enjoy based on what you know about the readers in your classroom and your knowledge of new titles. Getting students to promote a favorite book can ignite an excitement for a title, book series, genre, or topic that will ensure the book is read by their peers.

- Book Blurbs written by students and placed inside the front covers of books are often a welcome surprise. Students share their opinions as well as a short blurb on a 3×5 card and place the recommendation/blurb inside the front cover. Students sign their work. This allows readers to share ideas and discuss the text later. Students can also place sticky notes directly on the cover with a short recommendation (i.e. If you like eerie books that will keep you awake at night, you have to read this book!)

- Consider creating a “if you liked this book… try this next…” shelf. This allows students who enjoyed a genre or series the opportunity to try something similar yet different. It can help expand the readers’ reading repertoire and help build new reading interests. Your school librarian can help you gather books and can give you newer titles.

- Book Talks given by students introduce books and create an excitement for reading. Research by Williams and MacDonald (2017) shows that peer recommendation is a powerful way to get kids to read. Welcome to Reading Workshop: Structures and Routines that Support All Readers offers examples and formats you can use to help students book talk in your classroom.

- Book Reviews can be modeled by the teacher and simply displayed on a bulletin board or on the class website. Students can write a review for extra credit or in place of certain assignments that are designated by you as possibilities where students can substitute a book review. Some students may choose to post a review on Amazon, GoodReads, or other public venues.

- Creating special displays once a month to spotlight an author, new books, a specific genre, or a specific topic. Here’s a chance to highlight books to grab your students’ attention. Nonfiction displays are valuable – highlight books about climate change, space travel, and immigration.

Supporting Summer Reading with Your Library

Reading is probably the most important thing kids can do in the summer. There are many summer reading programs offered by local public libraries. There are summer reading camps and online summer reading programs, too. So, how can you help your students continue to read over their vacation in ways that other programs may not be able to do?

First of all, no one knows your students better than you do. Build summer readers by helping them choose a book from your classroom library that they cannot possibly put down. To accomplish this task, make sure your library collection has multiple copies so best friends can both choose to sign out the same book. Your library should be home to many series books. What happens when you read the first book of a series and love it? Will you look for the sequel? Reading books in a series helps students be successful. They get to know the characters, how they react, how the plot goes, and all that knowledge helps them read the next book, and the one after that. Before they know it, they’ve polished off two or three books. Wow! Encourage students to form summer book clubs and partnerships – The Hunger Games, The Maze Runner, Harry Potter. Sometimes, a benefit to a series may be that there’s a movie or two about the book. A summer movie night after the book is read – possibly to be enjoyed by family and/or friends!

Help your students set a goal for summer reading before the end of the school year. Perhaps some students want to explore a new genre such as science fiction or poetry. Some students may set a goal pertaining to how many books they read or how many minutes per day will be devoted to reading. You can provide easy access by creating a sign-out system and letting your students choose one, two, or more books to take home over the summer.

Final Thoughts

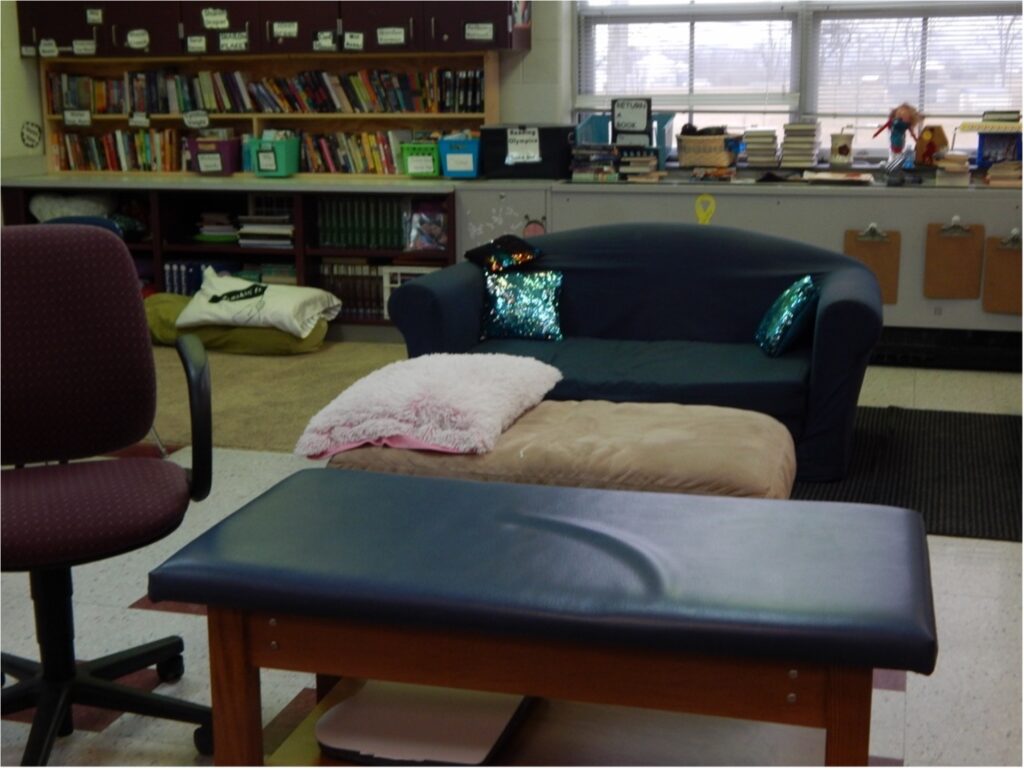

A classroom library can be the hub of your community. It has the potential to buzz with excitement when books are carefully chosen and strategically displayed. So often, it seems like the teacher is the curator/owner of the space. Yet when we hand over the responsibility to our students, the space becomes something they own and want to use. Inviting students to suggest book titles based on their interests and expertise will help diversify your collection. Letting students create spaces around the classroom to display books and organize and label the shelves in a meaningful way for them will help your library appeal to the entire community. A library is more than just a corner of books; it can be a place to sit and quietly read for research purposes or pleasure. Ask your students to help design a space they would find comfortable and inviting.

Stop and Reflect:

- Is your library being used? Do students utilize the classroom library to get reading material for pleasure? For research?

- What steps can you take to make your classroom library a place students want to use?

![]()