Reading the World: Nurturing A Global Perspective for All Students

By Laura Robb

Books give a soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, and life to everything. Plato

“The only way to read the world is by traveling the world!” Unprepared for these words recently spoken by a first-year teacher during a collaborative conversation on independent reading, I delayed responding. As everyone filed out of my office, I asked the teacher to remain. He insisted that travel was better than reading books—it was “direct” experience, not reading about the experiences and lives of others. My issue with these beliefs is that they affected independent reading in his seventh-grade classroom: The twenty minutes a day required of ELA teachers occurred from zero to two to three times a week. My concern with his reasoning revolved around depriving students of access to books—having opportunities to choose and daily read culturally relevant books that reflect the diversity in our country and the world.

Access and Opportunity Can Lead to Equity

Access means that students can self-select books from a range of genres and reading levels that they want to and can read in their classroom and school libraries. Classroom libraries put books at students’ fingertips, allowing them to return a completed book any school day and browse to find a new one. A well-stocked starter classroom library has 600 to 700 culturally relevant books on a wide range of reading levels and genres. Over time, the goal is to have 1,000 to 1,500 books that include recommendations from students, transforming the collection into our library.

Access can lead to equity as long as classroom and school libraries have culturally relevant books that permit all students to read and learn about diverse cultures and lifestyles. In addition, course opportunities, books, materials, technology, and professional learning are also factors influencing access and equity in schools. The most inclusive schools tend to focus on how staff can create opportunities that reach and meet the needs of all students no matter their socio-economic status and/or reading abilities.

To read is to know people and places we’ll never meet. To read is to step inside a character’s skin and live life as that character. To read is to visit the past, live more deeply in the present, and glimpse into the future. To read is to know our selves better by knowing and empathizing with others. To read the world, students from all cultures and ethnicities need access to books that represent the diverse populations and lifestyles in our country and across the globe.

Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors

While many teachers and school leaders continue to dedicate themselves to developing classroom libraries and curricula that include culturally relevant texts, there is still much work to do. One pathway to creating better opportunities for students is to consider the role of books in your school using the reflections of Rudine Sims Bishop:

“Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created and recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror. Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection, we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience. Reading, then, becomes a means of self-affirmation, and readers often seek their mirrors in books.” (1990, p. ix-xi)

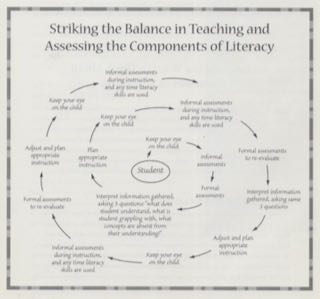

You can meet the diverse reading needs of students in your classes by providing access to culturally relevant and diverse texts, daily including independent reading, and then offering them opportunities to choose what they want to read. Then have students engage in partner and small group discussions because reading is social.

Reading is Social: Give Students Choice and Voice

Recently, I finished reading The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller and at different points in the book I felt compelled to reach out to a friend to discuss my feelings. Through impromptu conversations with classmates and friends, readers satisfy a desire to share books. Yes, reading is social and it’s important for teachers to keep in mind that besides choosing their books, students crave opportunities to spontaneously share a favorite part or comment about their book with a peer.

Besides formal partner and small group discussions, set up independent reading so that students can be social and have whispered, unplanned talks to express their feelings and/or thoughts about a book. Independent reading is often not silent nor is it noisy. Instead, the sharing is spur-of-the-moment, and students might ask a classmate to listen to a powerful passage or explain an emotion or a connection to a character or event. The social aspect of reading is also a terrific way to advertise beloved books to peers!

Thoughts That Linger

When students have choice and voice, they engage deeply with texts. Encourage them to stack a few “I-want-to-reads” in their cubbies, keeping books at their fingertips, so they can start a new book after finishing and returning a completed text to their classroom library. By offering all students choices of culturally relevant books that interest them—books that they can read, enjoy, and talk about, you move a step closer to the access and equity that is the civil right of all students. Moreover, you provide reading experiences that prepare them to participate productively in a global society.

References

Sims Bishop, Rudine (1990). “Windows, Mirrors, and Sliding Glass Doors,”

Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3), ix-xi.

Miller, Madeline (2012). The Song of Achilles. Boston, MA: Back Bay Books.

![]()