There’s Power in the Reflective Reader and Writer

By Cameron Carter

As teachers, we make thousands of decisions a day. We often reflect on these decisions and wonder, “Was the decision I made the right one?” or “How could I have done things differently?” We continually question ourselves in order to grow.

Just as we model what we teach to students, it is imperative to model how to be a reflective learner, especially in the areas of reading and writing. Reflection can be directly linked to critical thinking and creativity, which outlined by Battle for Kids, are the top 21st century themes for every student around the world.

Connect Reading and Writing Through Reflection

I’ve stated in prior blogs, “Reading and writing are interconnected processes woven together like a beautifully, intricate spider web.” Reading and writing are not rivals or isolated islands. I’ve been asked, “What’s your specialty, reading or writing?” My response is always the same: both. In my philosophy of literacy, I cannot, and will not, separate the two. Yes, I have strengths in reading, and yes, I have strengths in writing, but I would never think to place one above the other.

A powerful tool that is embedded throughout reading and writing is reflection. Teachers can model reflection orally or through written expression. Reflection will look different for each and every learner.

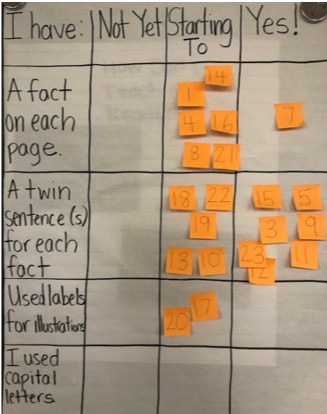

In our first grade classroom, we use the Units of Study as our writing framework and resource to dive deeper into the genres of narrative, informational, and opinion writing. In each genre, students revise their pieces using the rubric and checklist created by the Teacher’s College Reading and Writing Project (TCRWP). In doing so, the students reflected upon the goals set by TCRWP, and decided to use their own language to create the goals connected to the particular genre we were writing.

The students, each with their own special “magic number”, reflected on each goal as they moved through the checklist evaluating if they were in the “Not Yet”, “Starting To”, or “Yes!” column. Students reflected with me during conferring time, and students also reflected with one another. On some days, students even reflected independently. We had many conversations regarding the writing process, using this statement: “Writers are never done; they’ve just begun!” First-grade writers knew that the checklist was a continuous, flowing anchor, which allowed and encouraged them to move their Post-It note to where they were in their writing pieces.

Each and every day, we come together for our “Share” portion of “Writer’s Workshop.” This is when most of the power of reflection comes into play. Students share what is going well for them during their “work time,” and they share challenges they are facing in certain areas of their pieces that connect to the student-created checklist of goals. It has been incredible to see, over time, how students have grown in sharing honest reflections that truly improve their writing.

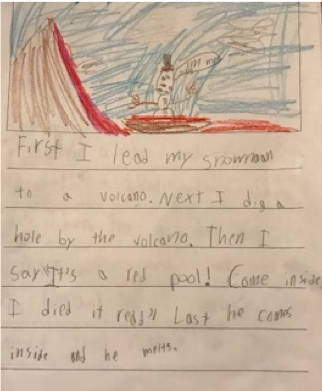

Not only have we applied reflection within our Units of Study writing time, we’ve also embedded reflection when writing pieces that connect to a read-aloud. For example, this week, students inspired me to read aloud, How to Catch a Snowman. The students chose the read-aloud because it was a new arrival from Scholastic. After reading, we reflected on what should inspire our writing. The students decided they wanted to write a “How-to” piece–their own version of How to Catch a Snowman.

The voices of the students were strong, as they reflected on the important writing goals that should be connected to this writing piece.

As one can see, the writers chose goals that also connected to their prior writing experiences, such as unfreezing a character (adding dialogue) and using the signal words (first, next, then, last) to show a sequence of events.

In today’s busy world, reflection is more important than ever! We must model reflection for our students, just as we model how to read fluently or write expressively with detail.

Reflection helps us grow! Therefore it should be woven daily into reading, writing, and all content area lessons because reflection guides students’ process and supports growth across the curriculum.

Cameron Carter is a first-grade teacher at Evening Street Elementary in Worthington, OH. He is the former Elementary Lead Ambassador for the National Council of Teachers of English and the current Elementary Liaison for the Ohio Council of Teachers of English Language Arts. Cameron has a Masters in Reading and Literacy from The Ohio State University.

To continue learning with Cameron, follow him on

Twitter @CRCarter313

Facebook @EduCarter10

and

![]()