How Poetry Changed Nicholas’ Life

By Lois Letchford

Living in Brisbane, Australia, my six-year-old son, Nicholas, failed first grade. The effects of going to school showed themselves through his quietness, his bitten fingernails, and the daily wetting of his pants. His teacher shouted at him for his slowness, his withdrawal, and his inability to follow the “simplest instructions.” Testing revealed he could read ten words, displayed no strengths, and above all, had a low IQ. The prognosis was dire.

An opportunity arose for our family when my husband was offered a 6 month study leave in Oxford, UK. For our family this was a bit like déjà vu as my husband had completed his PhD there and where our eldest son was born. This trip allowed him to investigate the flow over the roofs of model buildings in the Oxford Large Wind Tunnel to better understand the mechanisms that lead to failure.

Planning to use this time to work with Nicholas in a one-to-one setting, I set myself up with a series of books entitled, “Success for All.” With a new environment and time on our side, what could go wrong. Well…isolated words on every page and no pictures did nothing to assist me in my teaching or Nicholas’s learning to read. It was an abject failure, and I was no better than his first-grade teacher.

Faced with a blank slate, and no excuses, I thought about Nicholas’ strengths. I knew he could rhyme words and see patterns in words and his environment. With only these known skills, I thought about writing simple poems based around consonant-vowel-consonant letter patterns and rimes. I chose words which rhyme with bug, such as mug, lug, tug, and rug.

Moreover, most poems for children are structured around a rhythmic pattern that Nicholas could easily detect. And, of course, poetry is a joy to read and easy enough that Nicholas could meet immediate success.

What a mug of a bug

he is to lug his rug along the kitchen floor.

Doesn’t he know his rug will tug

his good things out the door?

Together we talked about the meaning of the poem, found the rhyming words, and finally made illustrations for each poem read. The illustrations for the Mug of a bug poem began using different colored paper to create the bug and its rug, as our enjoyment for learning intensified.

The transformation in our little classroom was instant- no longer did I expect Nicholas to read anything. I read to him. One success led to another. And another. Everyday Nicholas was excited to read and play with yet another rhyme.

“I have a fun poem for you today, Nicholas,” I said.

“The cat in a hat sat on a mat with a rat and a bat.

Well, fancy that!

That is just not possible.

There might be one scratched cat, no rat or bat and one messy mat!” I read.

Nicholas sat, silently; his eyes fixed on the paper.

When Nicholas failed to comprehend, his immediate response was withdrawal.

My mind spun. “What do I have to do?”

“Nicholas, let’s act out this poem. What animal would you like to be?” I questioned. “The cat, the rat or the bat?”

“I think I’ll be,” decisions take Nicholas a long time, “I’ll be the cat!” he says with a slight grin.

“Okay, I’ll be the rat,” I continued.

“And I’ll get a stuffed toy for the bat,” he says as he ran off to find an appropriate animal.

He returned proclaiming “I’ve got a hat and a mat and a bat!”

Well this showed he was thinking.

“Now we can act the poem out,” I suggested. “What happens if a cat, a rat and a bat were in a hat together?” I asked standing beside Nicholas.

“They would fight!” he replied instantly, laughing. The lesson provided loads of chuckles and giggles.

I was learning about teaching as Nicholas was learning to read. It’s now an enjoyable experience for both of us.

Although the words are easily decodable, inference occurs at all levels of reading. Readers must make inferences in order to comprehend. We continued to recite our poems from memory as we walked his brothers to and from school. Later in the day we read them from the printed page.

Each day we worked to retrieve and read those rhymes. His brain was being lined with language and making connections between words and pictures. Using poetry, which at the early stage is short, repetitive, and focuses on rhyming, there is often the clear purpose of creating an overarching image. This allows the reader to feel they can grasp the image or message, however “silly”, quickly and enjoy the experience through the rhyming sounds they make in speaking the poem. In effect this image or message “cocoons” the reading experience and with repetition strengthens the understanding of the “whole” while building out the letter and word components.

The next step of finding rhyming words, allowed Nicholas to see and hear the pattern and actively encouraged him to recognize and manipulate the spoken parts of words. Finally, poetry allows for easy segmenting of words into their individual sounds. Each interaction with letters and sounds provided opportunities for strong foundational letter-sound associations, and helped Nicholas with many aspects of learning to read, thus the sounds “cocooned” within the whole, the rhyming pattern, and the individual word.

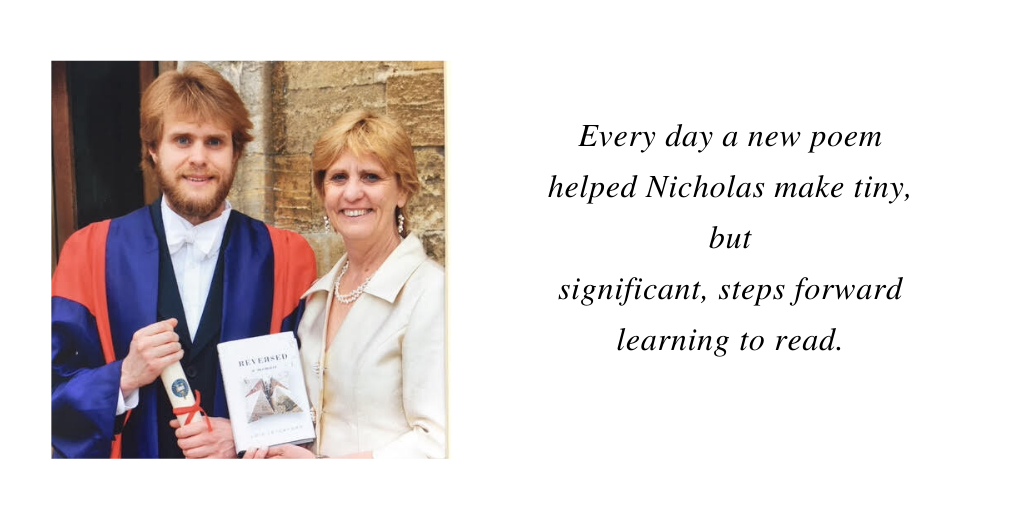

Every day a new poem helped Nicholas make tiny, but significant, steps forward learning to read.

After completing many poems using short vowel sounds, we moved on to more complex sounds — the oo sounds, as in cook, look, and book, captured my imagination. My focus turned to Captain Cook, the last of the great explorers. As an Englishman, he completed the mapping of Australia thereby presuming the founding of yet another British Colony. The words were simple, the ideas complex.

Captain Cook had a notion,

There was a gap in the map in the great big ocean.

He took a look, without the help of any book

Hoping to find a quiet little nook.

Captain Cook had a notion,

There was a gap in the map in the great big ocean.

He took a look and filled a whole book

That caused the world to look.

Living in Oxford and visiting museums, we encountered maps from the 1550s – ones that did not include our homeland – Australia

“Look, Nicholas,” I said, “there’s a gap in the map. There is no Australia.”

Our learning took a turn from writing simple word poems to writing poetry as an inquiry project.

I read books, all kinds of books, and turned my learning into poems for Nicholas. I found this was the best way for him to access information, and poetry made for easy repetition, for questioning and further tapping into his curiosity. Together we began to question – what knowledge did Captain Cook have when he left England for his explorations in the Pacific Ocean?

“Who came before Captain Cook?” Nicholas asked one day.

“That’s easy,” I replied. “That was Christopher Columbus.”

“And who came before Columbus?” he questioned.

I stopped. I was stunned.

Such a question had never entered my imagination, and for the first time, I knew my son did not have a “low IQ.” His questions told me he was assembling and processing information. He was “thinking.”

Being in Oxford, with the world of libraries and maps at our fingertips, we searched for answers. Viewing maps in the local antique map shops aided our search. Discovering that Columbus’s travels were based on the maps of Ptolemy, led us to visit the Bodleian Library of Oxford University, hunting for more answers.

Our investigation began in the gift shop, where a lady eagerly awaited our questions.

“Do you know where we could find a Ptolemy map?” I questioned, with an anxious Nicholas by my side.

The lady turned away from us, leaned against the counter, and scratched her head. Her eyes scanned the bookshelf. Finally, she bent down and retrieved a large, blue-covered book.

“This is a new book in our collection,” she said as she carefully placed it on the counter. “It’s a book of Ptolemy’s maps and is only recently printed. Does this work for you?”

Nicholas and I gasped.

“Yes,” I replied as Nicholas grinned and nodded.

Adding positive, enriching experiences to our learning enhanced Nicholas’s curiosity.

Our time in Oxford was completed with a memorable visit to the British Museum to see Captain Cook’s original maps which capped our epic inquiry project.

Returning to our home in Australia, Nicholas once again attended our local school. I was feeling on edge when I met with the school counselor.

“Nicholas learned so much! I wrote poetry and he was so excited by our learning,” I gushed.

“Well,” she replied, “he’s still the worst child I’ve seen in twenty years of teaching!”

Shocked, I left the room with my tail between my legs.

This was not the end of the story, just the beginning of a new chapter.

But what I found from this work with Nicholas was that poetry can be a wonderful entry point to literacy for children, especially the ones who find reading difficult. Poetry is fun to read. Poetry is easy to learn to read. Poetry contains word patterns that lays the foundation for phonics. Poetry is meant to be performed fluently and expressively, so it must be rehearsed (repeated reading). Poetry for children is easy to find, it is easy for parents and teachers to write, and it can be a great way to get children themselves into writing. In addition, poetry can lead to much deeper readings, explorations, and discoveries as it did with Nicholas’s study of Captain Cook.

Advice for parents whose children are like Nicholas:

Write for your children – write about their everyday experiences – what they see, hear, eat, or watch.

Write where you are with what you have.

Create books about their life.

Place the child as the central character of their story.

Take pictures to complement your writing.

Write in short sentences or poetry format.

Read and re-read to and with your child.

Recite the sentences or poems.

Record their reciting and send it to relatives – if possible, ask relatives to respond.

If a child has a challenge recalling a particular sound, find words and objects which include it.

Write and read every day.

Remember:

Learning is emotional, as well as cognitive.

When learning is painful, sadly, that’s what children learn.

When children are laughing, learning happens with ease.

Once the process begins, one never knows where it ends…

Postscript

Nicholas Letchford learned to read, thanks to his mother Lois and many fine teachers. Indeed, learning to read was only the beginning of his journey. In 2018, Nicholas earned a doctorate inApplied Mathematics from Oxford University in the UK. Lois became a readingspecialist in 1997, teaching children who had been left behind. She has also written about her and Nicholas’s journey to literacy in her inspiring book “Reversed: A Memoir,” which can be ordered through any bookseller.

Grab a copy of Reversed: A Memoir to read the full story at https://amzn.to/3d2cNg5

Reversed: A Memoir is her first book. In this story, she details the journey of her son’s dramatic failure in first grade. She tells of the twist and turns that promoted her passion and her son’s dramatic academic turn-a-round from “dyslexic” to PhD from Oxford University!

![]()